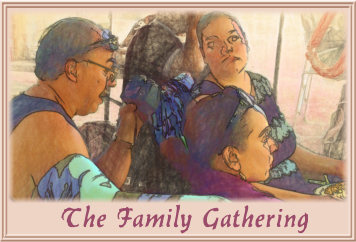

You’re at a typically crowded and raucous family get-together picnic. Uncle Weston’s voice hovers above the park, mingling with the smell of barbecue and camaraderie. Once again, he’s handing out wisdom to the young folks.

You’re at a typically crowded and raucous family get-together picnic. Uncle Weston’s voice hovers above the park, mingling with the smell of barbecue and camaraderie. Once again, he’s handing out wisdom to the young folks.

Uncle Weston loves to tell younger family members (like you) that you’re all misguided. Your mother was the one who set him off. After your mom tells Uncle Weston that you’ve been working on Tacoma’s Yes on Prop 1 campaign to raise the minimum wage to $15/hour, Uncle Weston rises up on his haunches, mounts his soapbox, inflates his bellows, and let loose with a mighty blast of wisdom.

![]()

Now you’ve always considered Uncle Weston to be a dyed-in-the-wool conservative, although he himself says he’s just a realistic adult. He tolerates your lefty leanings, and he thinks your political instincts are naive, if well intentioned. He says, “You’ll outgrow this liberalism when you grow up.” He paraphrases the old adage, “If you’re not radical when you’re young, you have no heart. And if you’re not conservative when you’ve matured a bit, you have no common sense.”

Gently draping his not-entirely sober arm around your shoulder, he says incredulously, “Do you really want to raise the minimum wage to $15 dollars an hour!?!?”

“Look,” he says, “that just raises the cost of production, and either the employer passes on those costs to the consumer, or he reduces labor costs by cutting hours or firing workers! Do you want to pay $15 for a hamburger at McDonalds?”

You say, “But Uncle, historically speaking, rising wages have just not caused rising inflation or fewer jobs. A number of studies shows that.”

But this seems counter-intuitive to Uncle Weston. Uncle Weston says all those pointy-headed smart-alecs with their phoney-baloney statistics lack common sense. And Uncle Weston prides himself on being a man of common sense.

![]()

T o illustrate his point, Uncle Weston tells us about a village in an underdeveloped country. A rich nobleman actually owns most of the land. The villagers farm a community garden on the rich nobleman’s property cooperatively . On this garden, they grow basic necessities of life and also some fine herbal substance (known in the local dialect as “kiff”).

The rich nobleman takes the entire harvest and puts it into a storehouse. Every Saturday, he permits those village families who have worked the garden for 40 hours during the previous week to fill up one small wheelbarrow with life’s necessities. That’s just barely enough to feed the family for a week.

The nobleman’s religion forbids him from smoking kiff, and he is a man known for his upstanding virtue. So he sells it on the black market and uses the proceeds to improve the community garden and the entire village itself, and he makes generous donations to charity.

But the poor villagers feel somewhat malnourished, and they have a vague feeling that there’s something wrong with this picture. If only the wheelbarrows were a bit bigger, they could put more of life’s necessities in them, and life might be more bearable! The deal is they get to fill up the wheelbarrow every Saturday if they worked 40 hours the previous week. If they work 20 hours, they get to fill the wheelbarrow half way. But there are no rules about the size of the wheelbarrow.

Then Ned (who is one of the brighter village youths) gets an idea. “Why don’t I build big wheelbarrows and sell them around the neighborhood. Everyone could get more of life’s necessities on Saturdays. It’s a win-win situation!”

At this point in his narrative, Uncle Weston yawns, smiles condescendingly at you, and mentions what to him is the obvious point. He says, “Having bigger wheelbarrows doesn’t make the garden produce more plentiful, and the nobleman will either cut hours or fire some of the villagers because there’s not enough produced each week to fill all of those bigger wheelbarrows.” He says, “Likewise, if the minimum wage goes up to $15/hour, the employers will either have to raise prices, cut hours, or lay off workers, as this little story illustrates.”

![]()

Now Uncle Weston is no fool, but the narrative doesn’t show as much common sense as your uncle seems to think it does.

Uncle Weston’s story doesn’t take into account that the harvest varies. Sometimes it’s bigger, and other times it’s smaller. If there is great weather, if agricultural technology improves, if agribusiness creates advances in farm machines and fertilizers, then the crop yields gets bigger. The villagers don’t have to work as hard to produce bigger crops.

That’s also the way the economy works. Businesses grow and shrink. Markets change. Production technology becomes more efficient, and labor becomes more and more productive as a result.

The employer sets prices to what the market will bear. Therefore, wages don’t really determine prices. If businessman A raises prices too high, another businessman B will develop greater efficiencies and cut prices to out-compete businessman A. Moreover, more money in the pockets of low-wage employees translates into more demand, which results in greater production and creates more jobs.

It’s true that individual employers sometimes have to cut their profits a bit to compete. Then the employer may spend a smaller portion of her money on luxuries (like kiff, yachts, fancy automobiles, expensive cars). Manufacturers of luxury items will see lessened demand and shift manufacturing to produce necessities. That will have the tendency to increase supply of necessities and thus reduce prices. It will decrease supply of luxuries and raise those prices. And if producing more necessities becomes less profitable, more employers will switch back to providing luxuries.

So it’s the market that tends to shift prices toward the value of the commodity. Labor costs do not set prices. Here are some interesting facts.

According to the United States Department of Labor, a review of 64 independent studies shows raising the minimum wages has had no effect on unemployment levels. This is also the conclusion of a Florida International University study.

A coalition of businesses and individuals called Businesses For A Fair Minimum Wage concur. They realize that more money in the pockets of low-wage workers increases demand. That’s partly why this latter group has circulated a petition calling for a raise in the minimum wage. Over 1000 of their member businesses and individuals have signed this petition, including such businesses as Costco, Eileen Fisher, Ben & Jerry’s, Stonyfield, and Dansko Footwear. They seem to think this will help create jobs and moderate inflation.

So, if you’re feeling a bit cheeky and naughty, you can ask Uncle Weston if he thinks he’s smarter and more successful than the members of the Businesses for a Fair Minimum Wage.

Ask him why he’s not rich if he’s so smart!

If you still need more ammunition, you can mention that in 1998, Washington State voters approved Measure 688, which pegged the minimum wage to the rate of inflation, resulting in the highest state minimum wage for more than 15 years.

During the campaign to approve Measure 688, the same pundits who now oppose Tacoma’s Proposition 1 predicted inflation. They said Measure 688 was a “job killer.”

Yet despite corporate wailing, kvetching, gnashing of teeth, tearing of hair, and whimpering about how unfair this was to the employers and how Measure 688 would drive businesses to take flight to more enlightened states with more pro-business attitudes, the economy thrived. The “People’s Republic of Washington State” continued to enjoy a boom for years, with only negligible deviation from the national rate of inflation, for nearly a decade. CNN Money describes a bit of this in a story about how Washington State benefits from a higher minimum wage 17 or so years later.

Next time you see Uncle Weston, refer him to the above links and tell him that more worker-friendly policies will increase demand, which will make the garden grow.

Pretty self-indulgent writing, don’t you think? I came to this website looking for a smart rebuttal to the Tacoma Weekly’s opinion column against this campaign, but this article just fuels more political division.

Lou,

My apologies for taking 7 days to approve this. The email that you had made this comment ended in my spam box, and I didn’t notice that you had made this comment until just now.

I’ll not comment on your characterizing the writing as “self indulgent” as I happen to be the author of the piece, and this article is what it is. But thanks for taking the time to check this website out.

What about employees that worked their way up to $15/hr? Will their wages go up 58% also? Or will their job with increased responsibility stay at $15/hr while the entry level jobs with less responsibility also pay $15/hr? Thank you in advance for your response!

Thanks for the question and thanks for writing, Alyce.

Proposition 1 only deals with the minimum wage. It sets the floor, not the upper levels. The answer about how much other people’s wages go up will depend on the arrangement employers and employees work out after the new law takes effect. You’re talking about what economists call “wage compression,” and it may be a temporary phenomenon after Prop 1 becomes law.

Anybody making just slightly above $15/hour now, who has been at the same job and worked their way up, has undoubtedly proven the value of their work. Such people likely will be in a stronger position to ask the employer for a raise.

“Entry level” jobs no longer exist in the sense they did 30 years ago. Half of Tacoma’s workers make less than $15/hour, and their average age is 36. A large percentage are in families that depend, at least in part, on their income. A huge percentage of public assistance goes to working people who can’t make ends meet. A raise in the minimum wage would cut down on public assistance, would help the economy as workers would have more disposable income to spend in local businesses.